1. Introduction¶

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/romankphoto/

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/romankphoto/

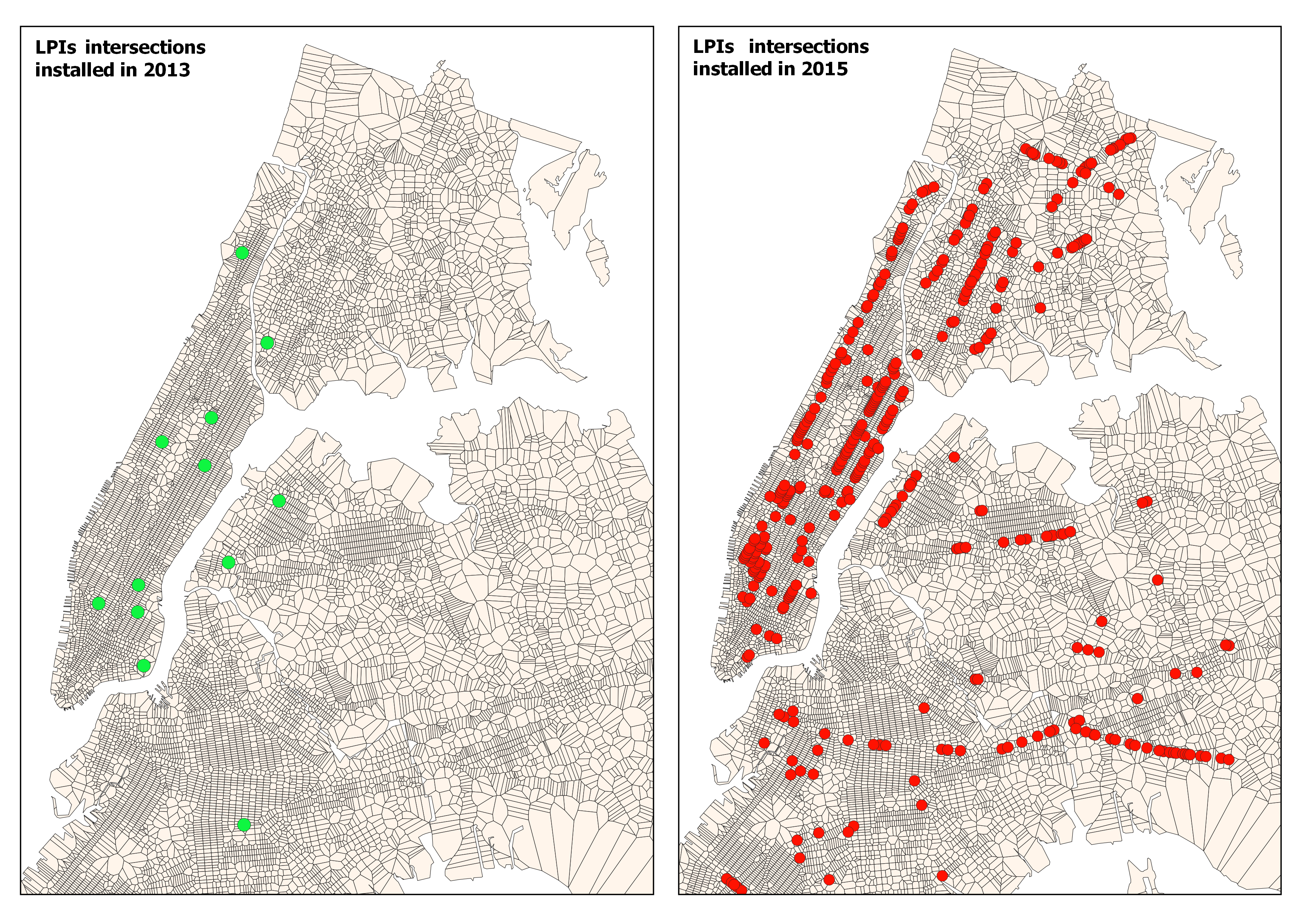

Leading Pedestrian Interval Signals (LPIs)¶

Source: https://nacto.org/publication/urban-street-design-guide/intersection-design-elements/traffic-signals/leading-pedestrian-interval/

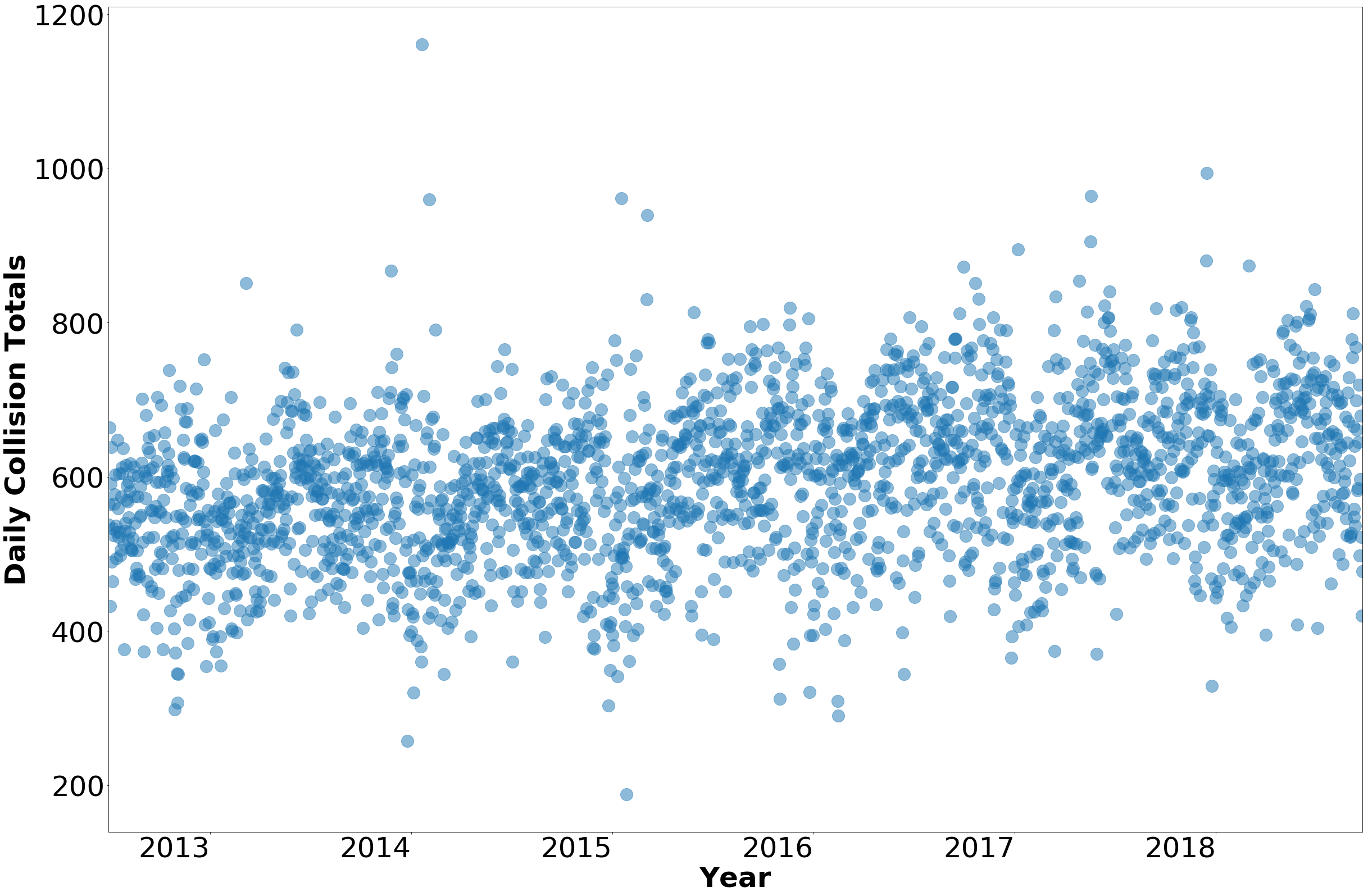

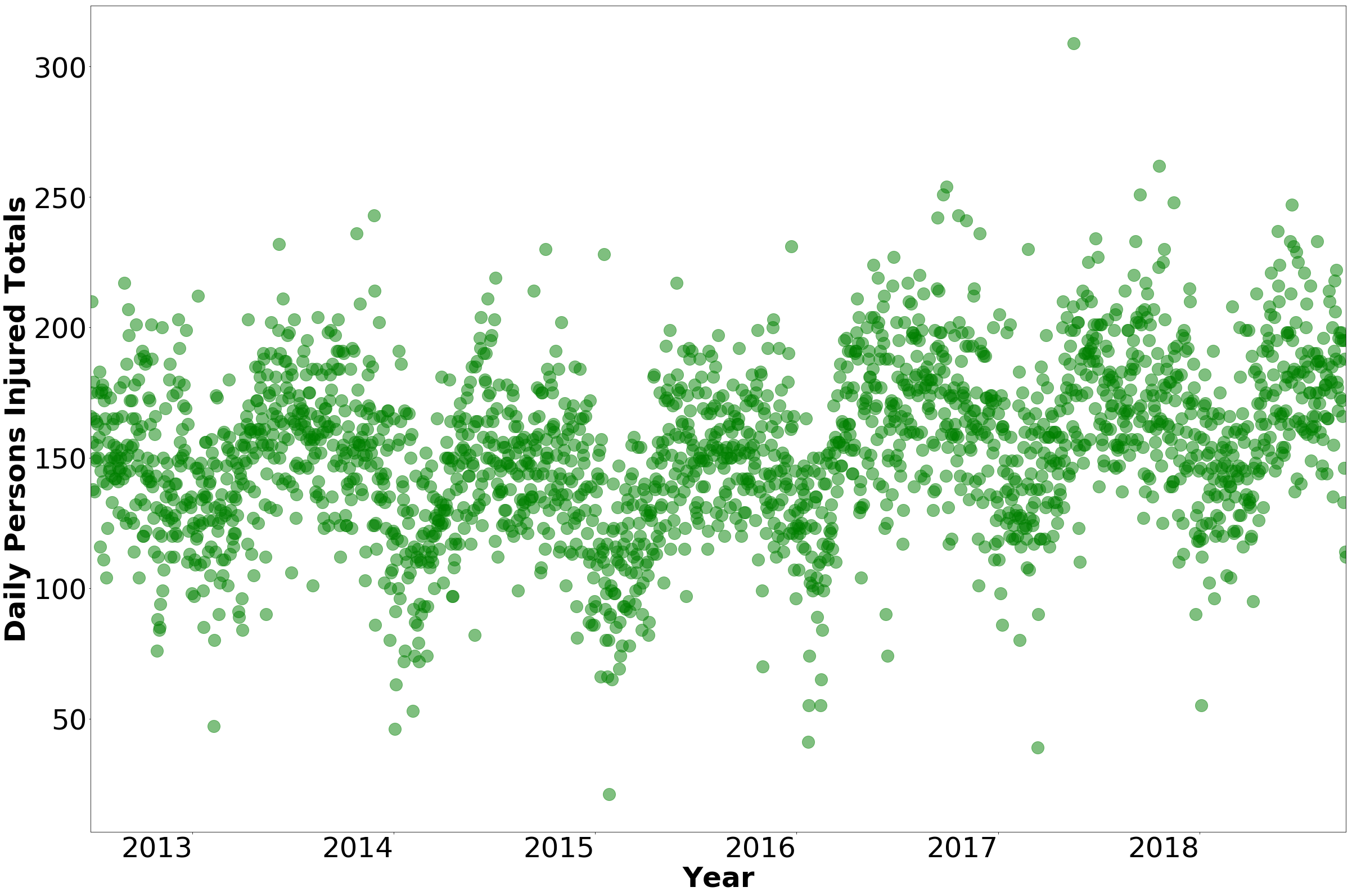

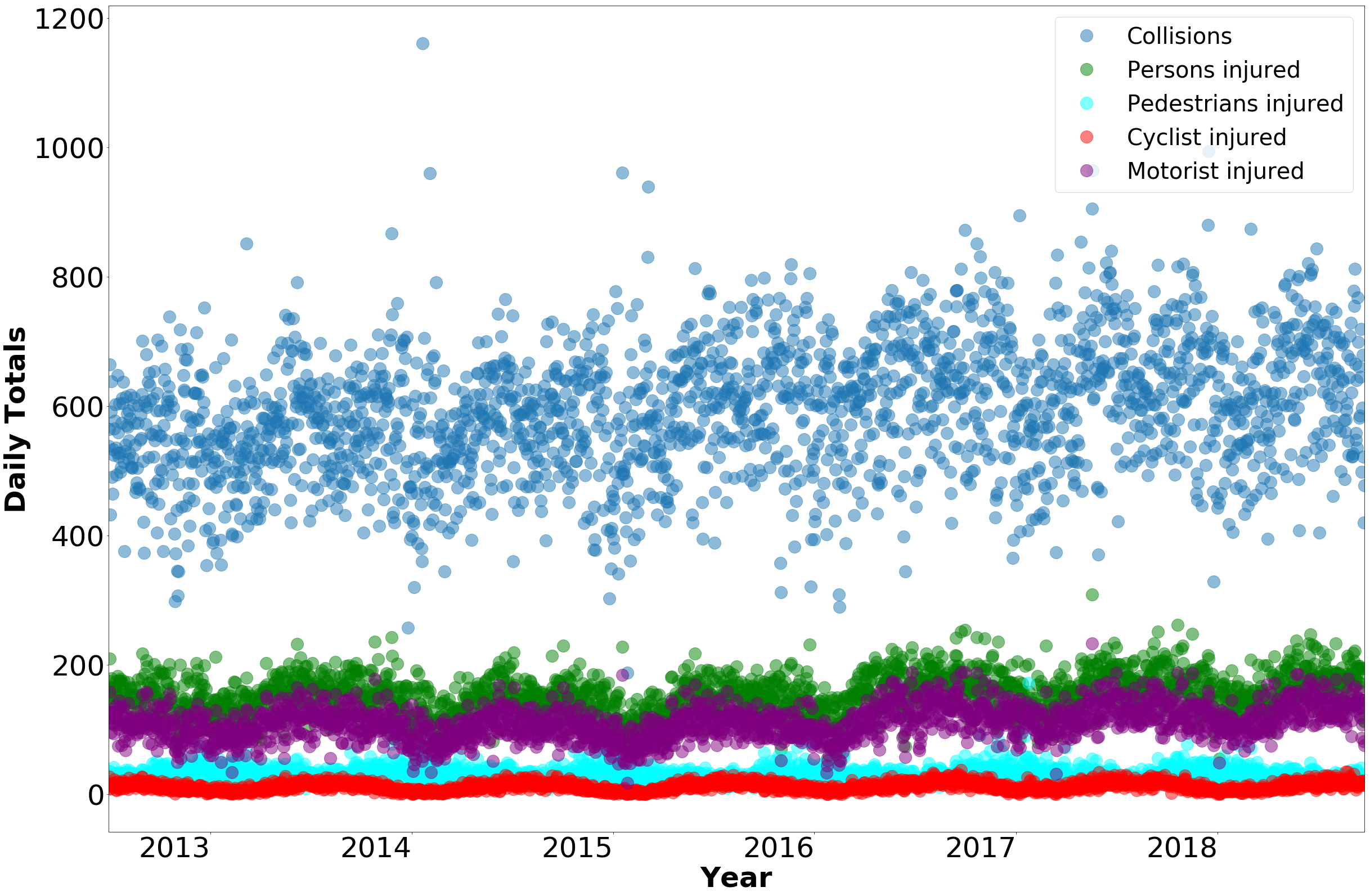

NYPD Motor Vehicle Collisions¶

- From July 2012 to September 2018

- Approximately 1.35 million collisions were recorded

Includes:

- collision outcomes, coordinates, streets, borough, zip code, time, vehicle type, contributing factors

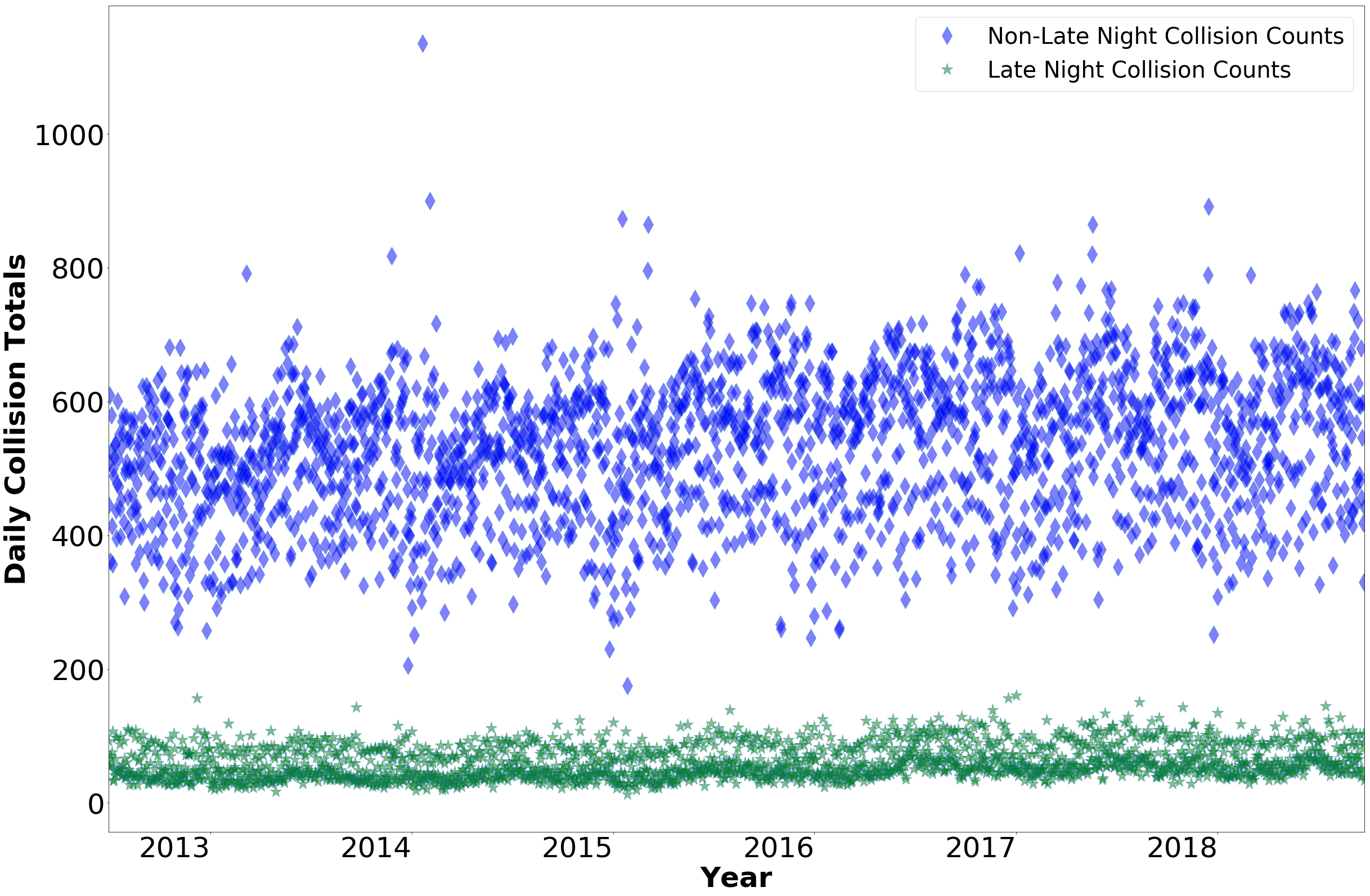

Stratified:

- 11.00 p.m. to 4.59 a.m.

- 5.00 a.m. to 10.59 p.m.

Hypothesis¶

The introduction of LPIs reduced collisions and injuries

2. Challenges and Solution¶

Selective implementation¶

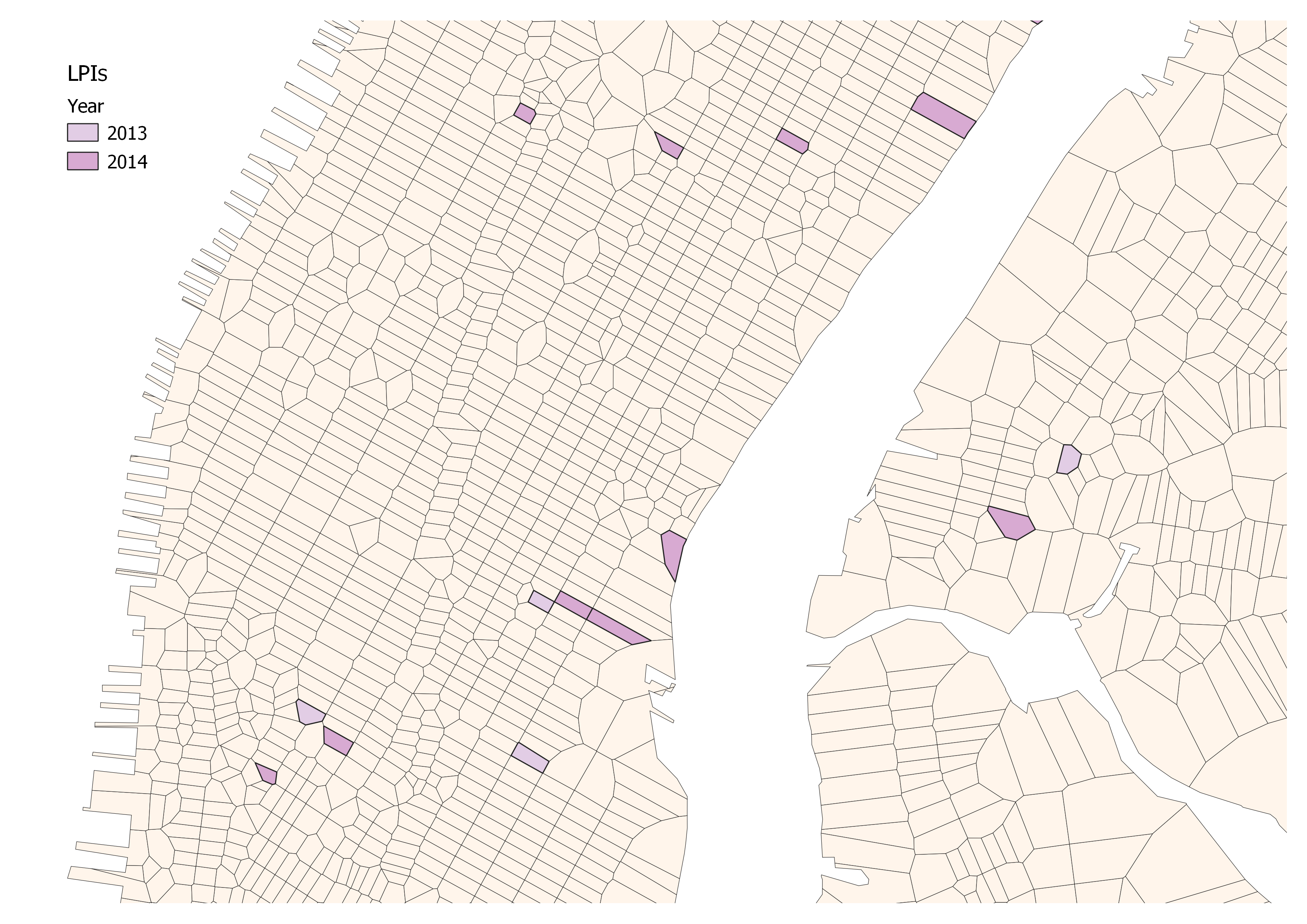

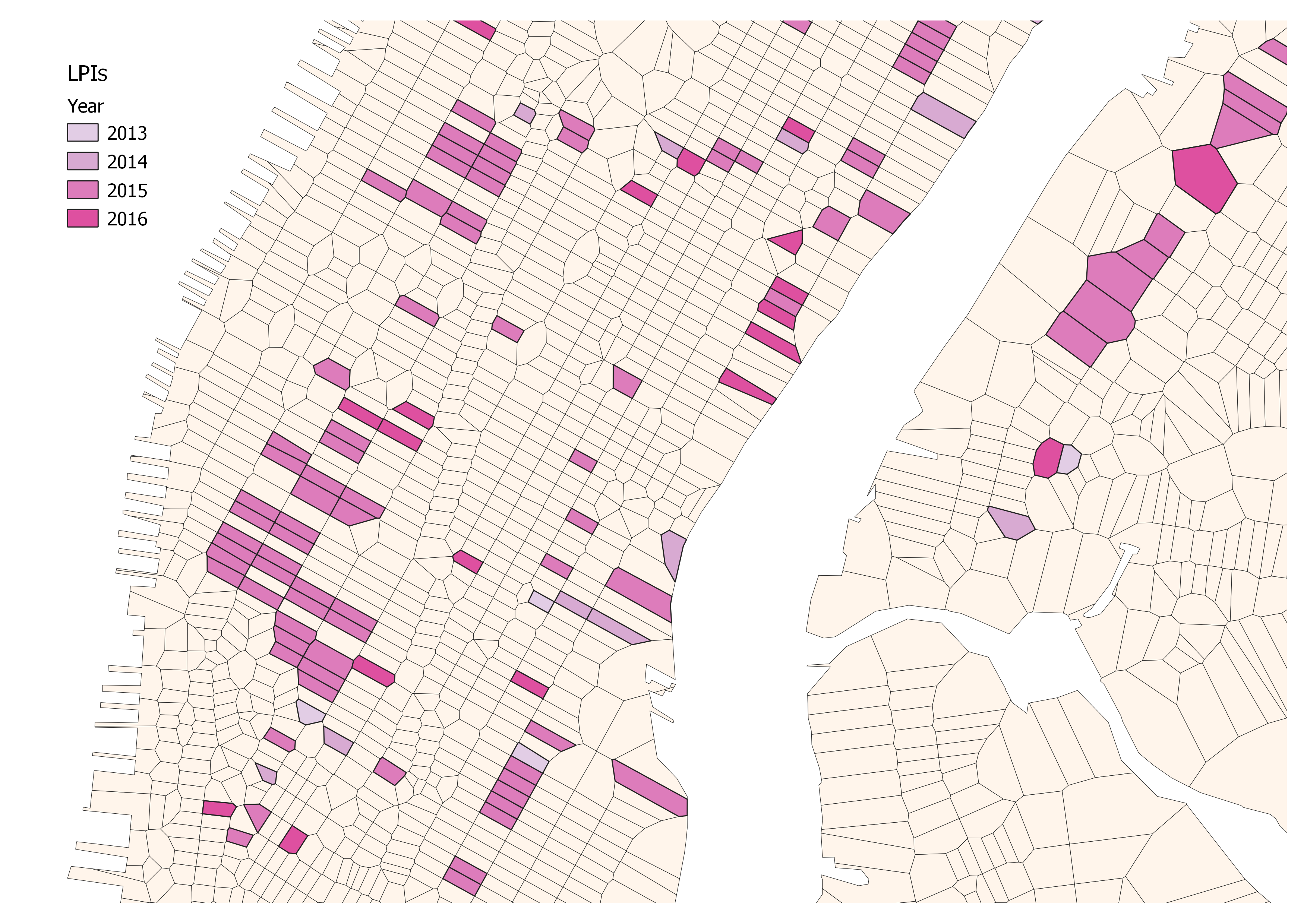

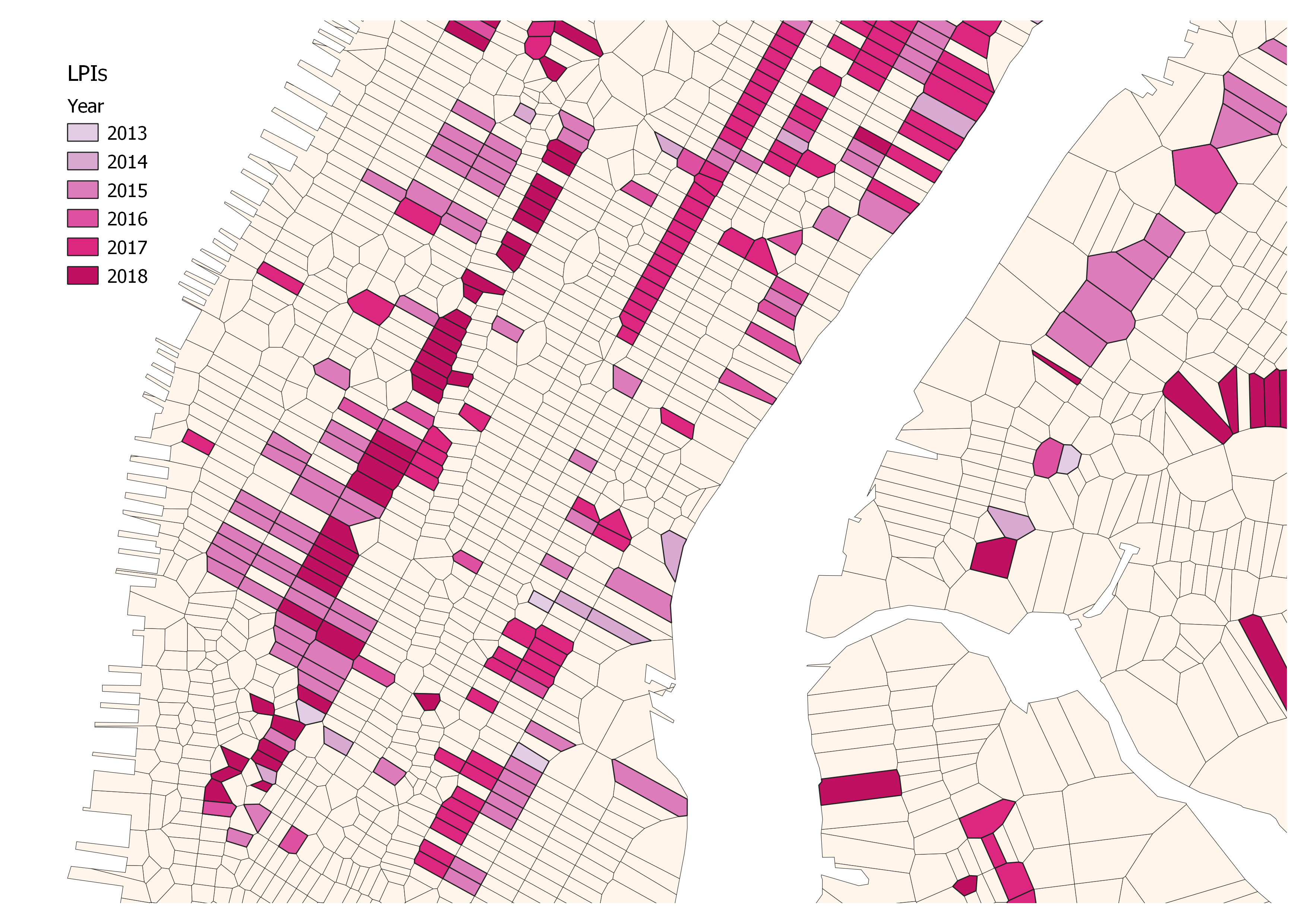

Phased introduction¶

Phased introduction¶

Phased introduction¶

Unobserved heterogeneity¶

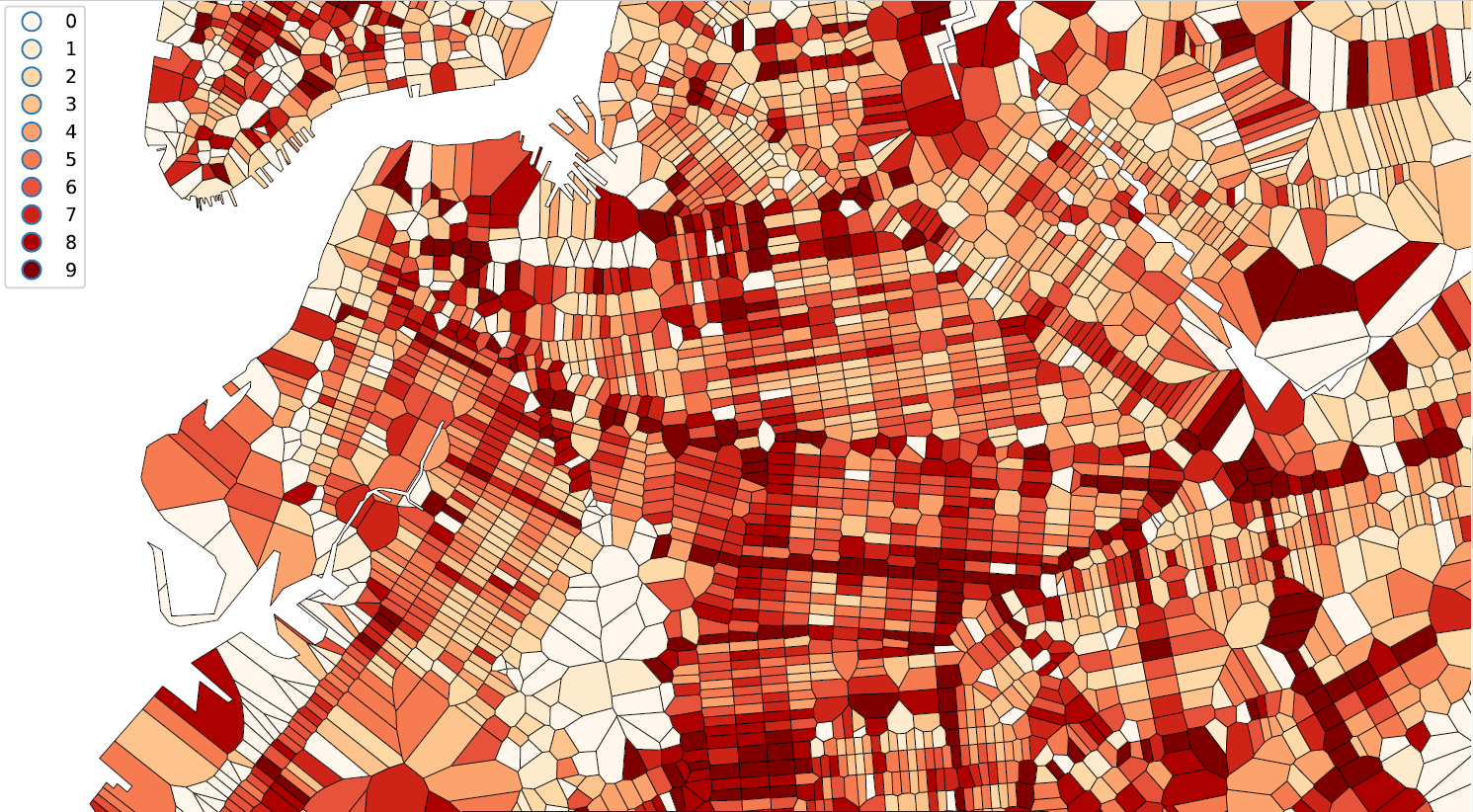

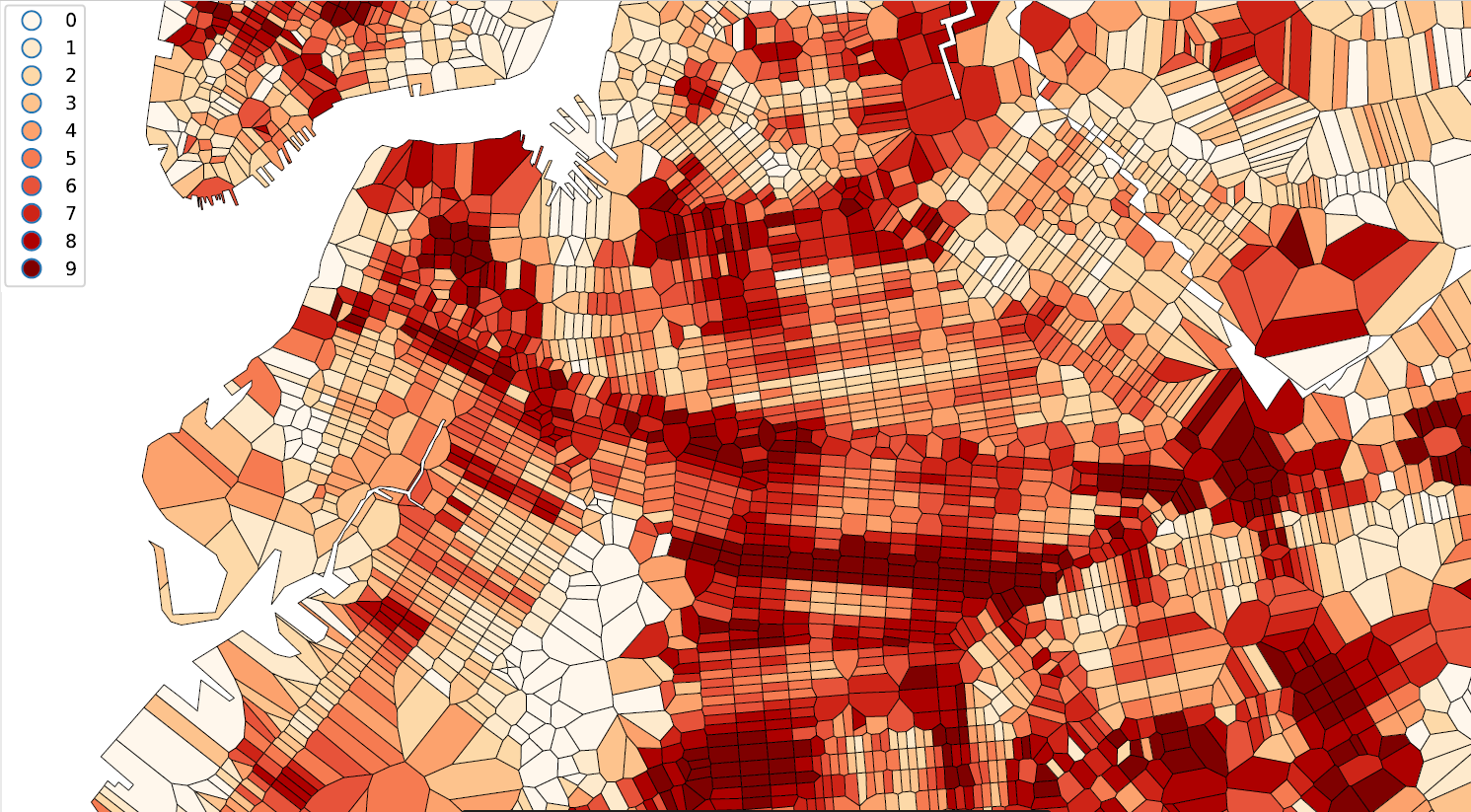

Spatial autocorrelation¶

Spatial autocorrelation¶

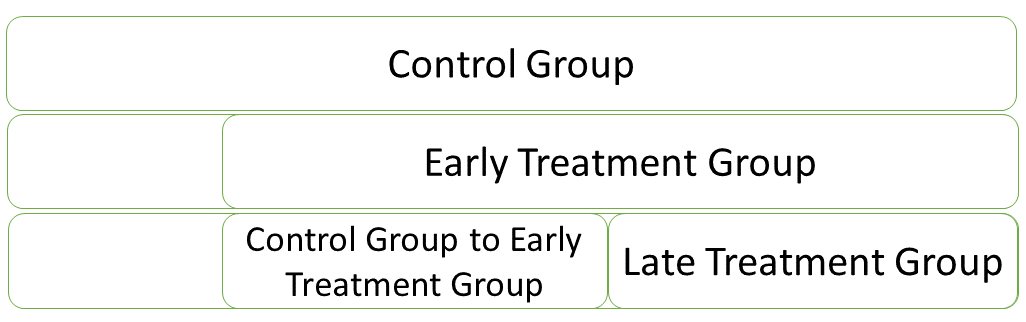

General Binary treatment Difference-in-difference model¶

- Simplifying from 25 quarters, we can think of it as there being 3 different groups

- untreated group $U$

- early treatment group $k$ that receives treatment at $t^*_k$

- late treatment group $l$ that receives treatment at $t^*_l$

General Binary treatment Difference-in-difference model¶

Assumptions¶

- Unmeasured determinants of the outcomes were time invariant or group invariant

- Common trends assumption

- Timing of the treatment implementation must be statistically independent of the potential outcomes distributions, conditional on the group-and time-fixed effects

3. Results¶

Model Specifications and controls¶

- Indicator for when intersections received LPIs intervention

- Indicator for when Bike route was built

- Indicator for when Street Improvement was implemented

- Indicator for when Left Turn intervention was implemented

- School Zone trends

- Senior Zone trends

- Priority Intersections trends

- Time effects

- Intersection fixed effects

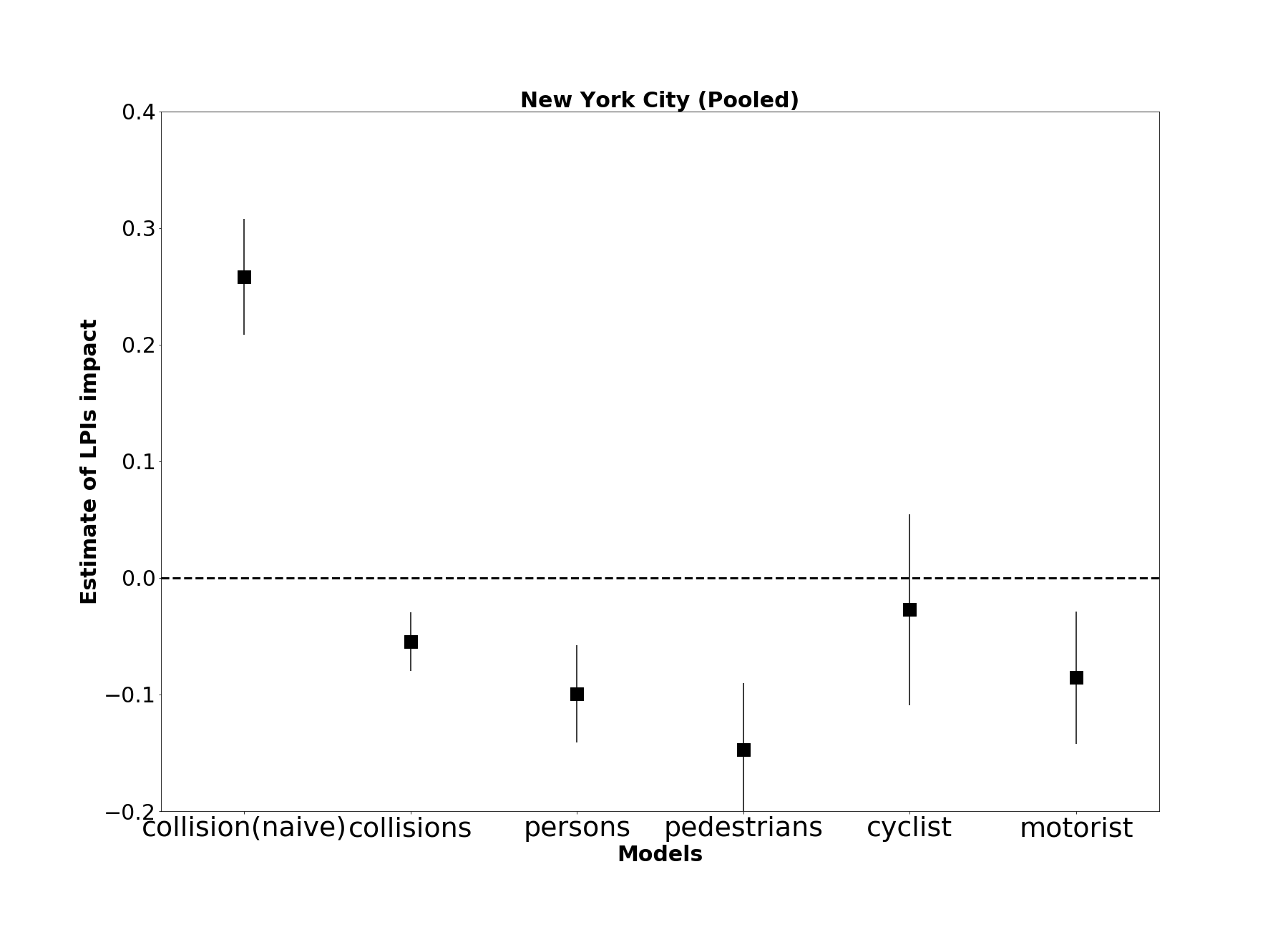

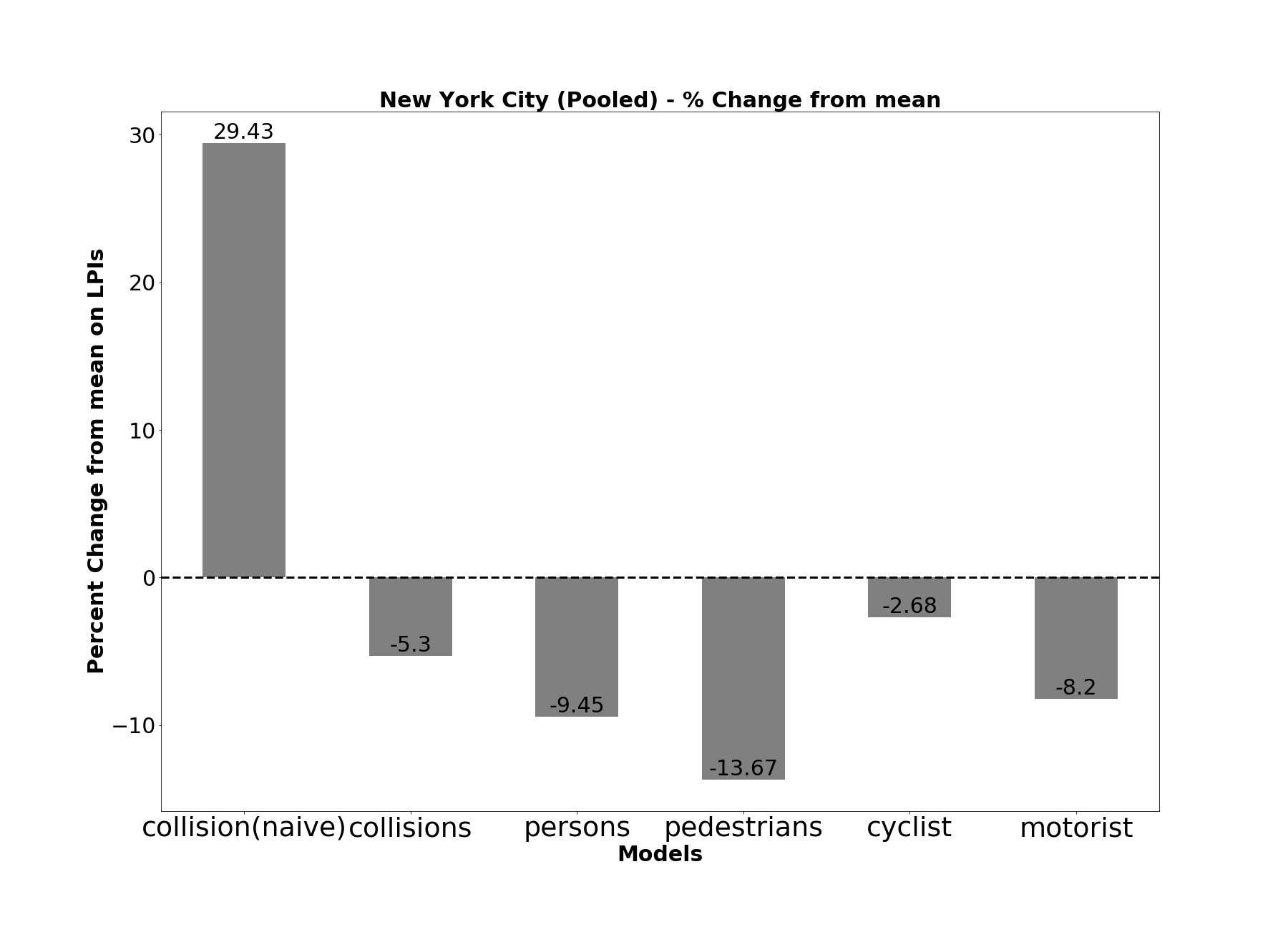

NYC Fixed effects DiD (Pooled)¶

NYC Fixed effects DiD (Pooled)¶

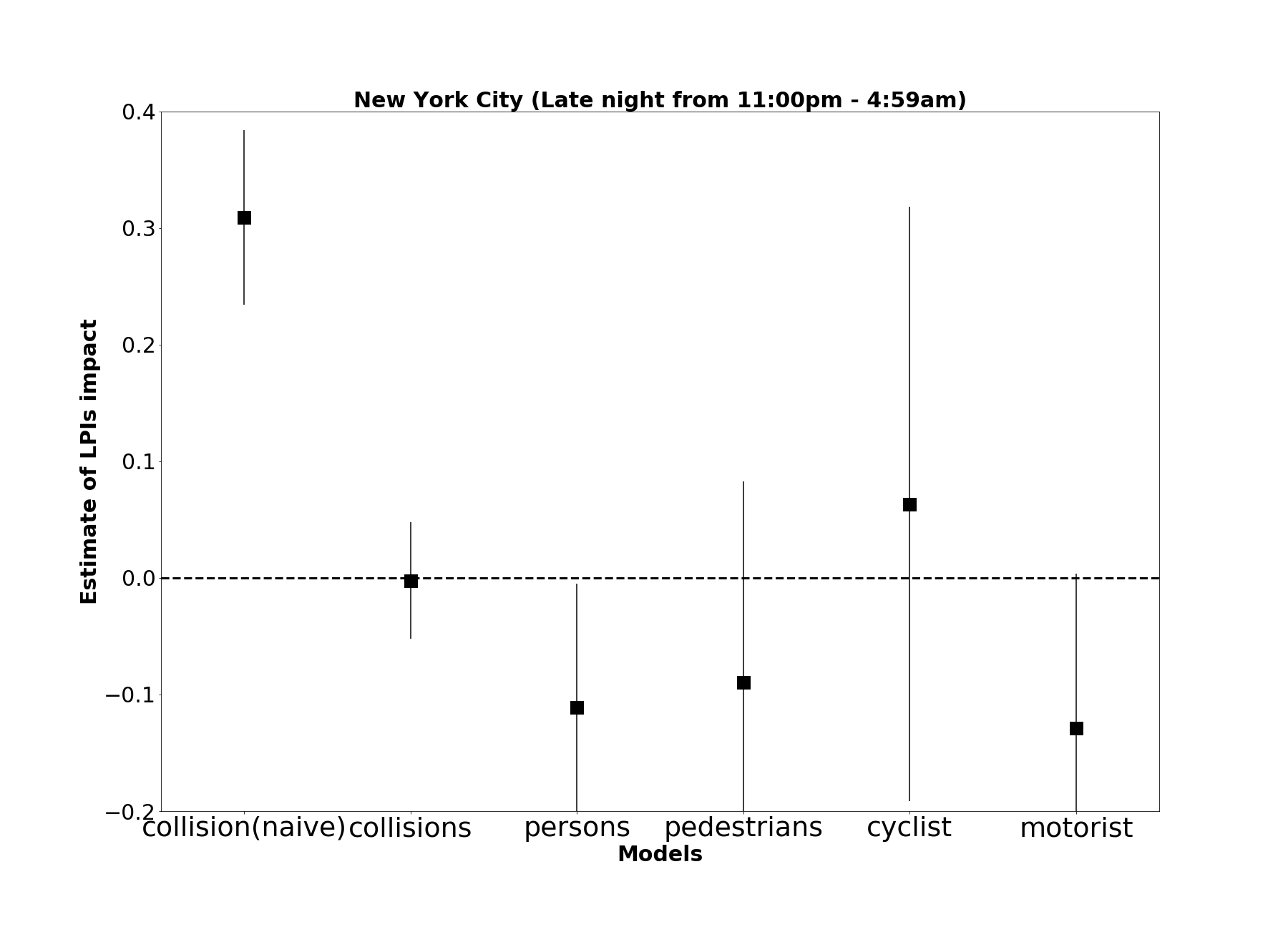

NYC Fixed Effects DiD (Late Night)¶

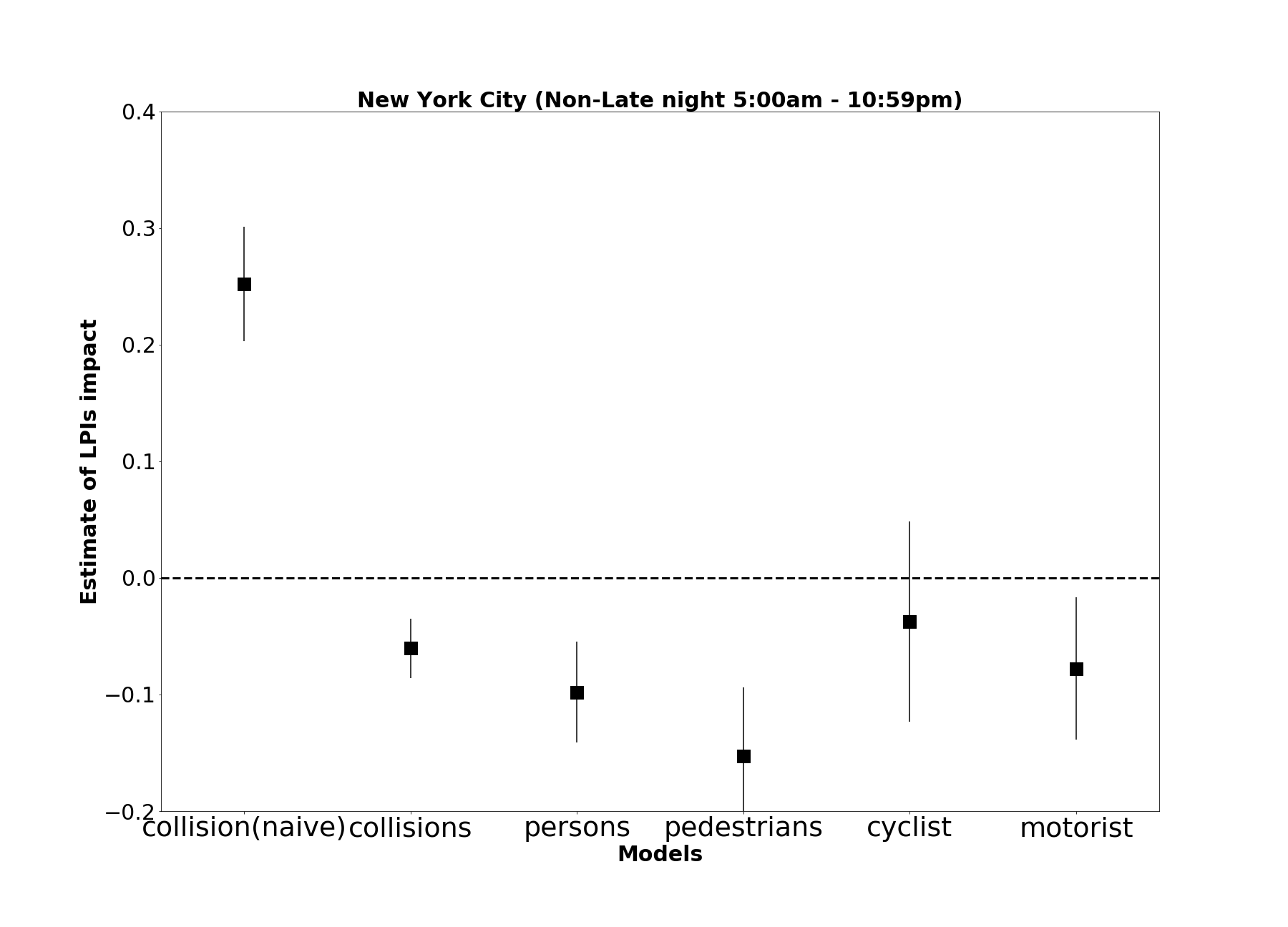

NYC Fixed Effects DiD (Non-late night)¶

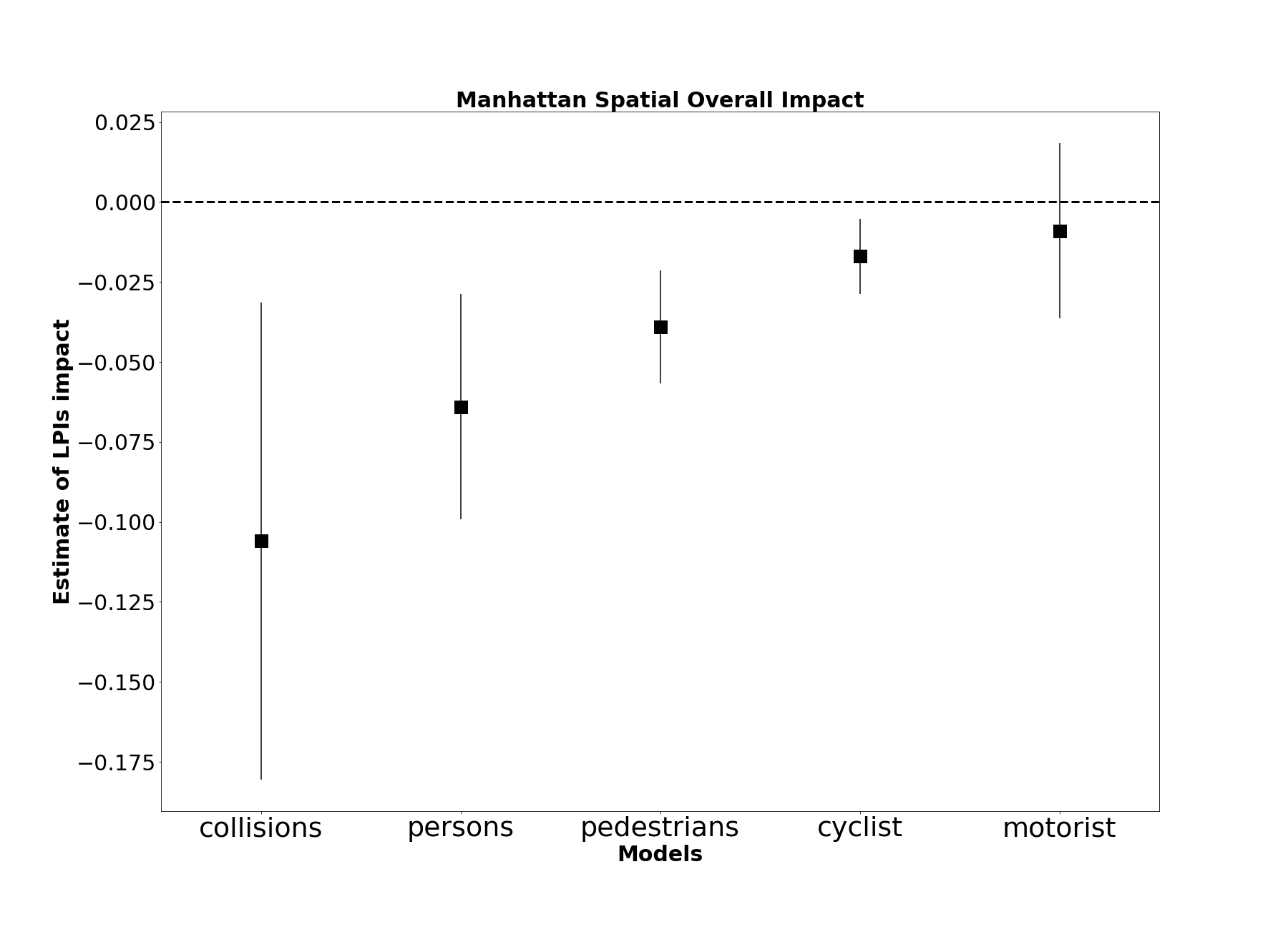

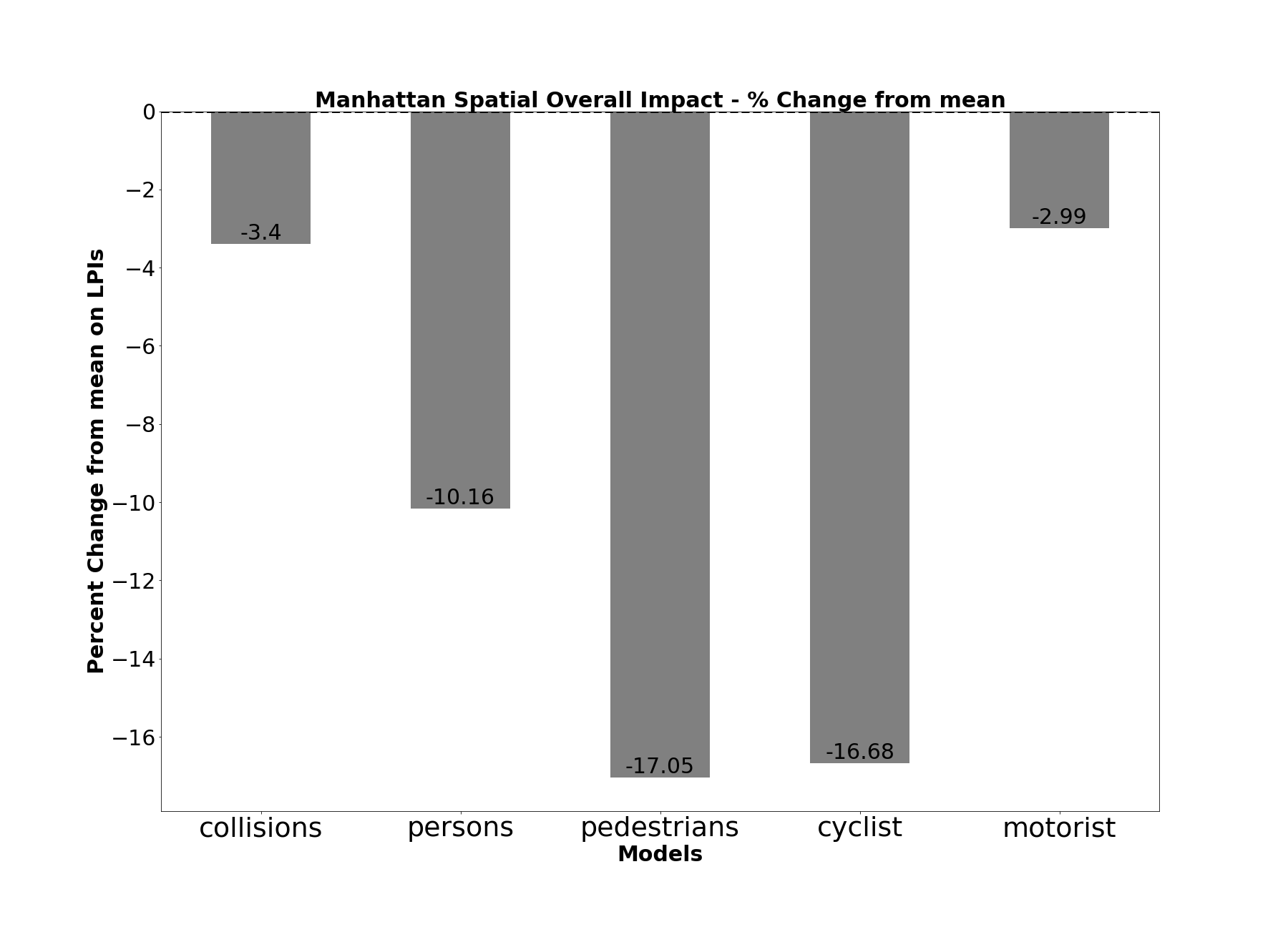

Spatial Lagged Overall Impact Fixed Effects DiD (Manhattan)¶

Spatial Lagged Overall Impact Fixed Effects DiD (Manhattan)¶

Tables and Figures¶

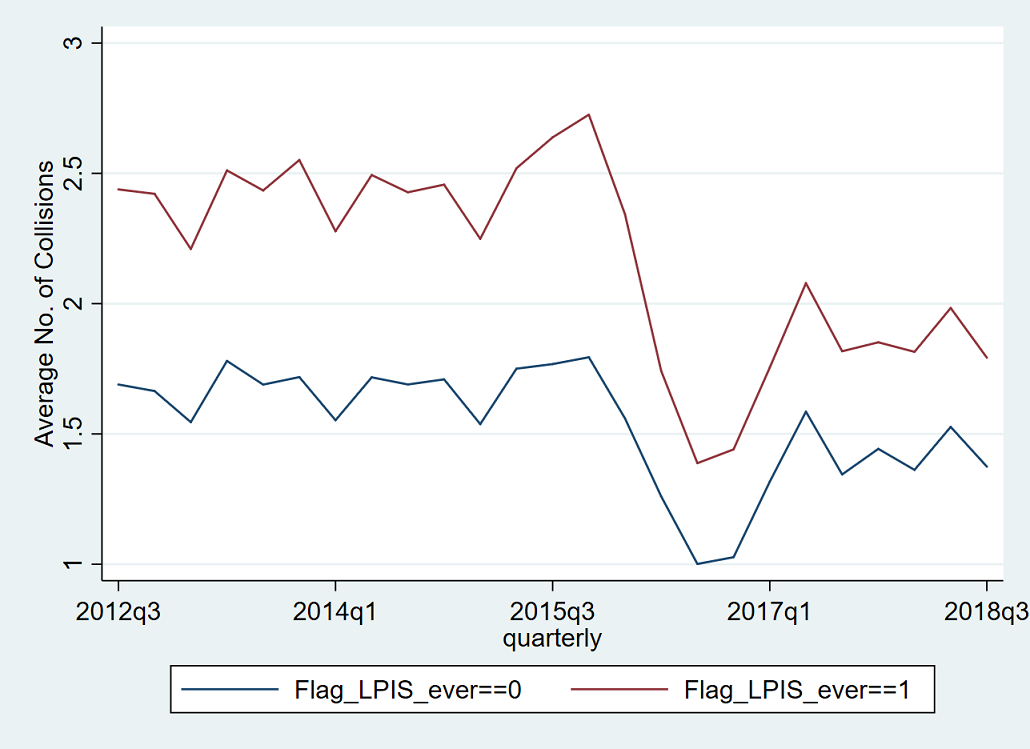

Table 1: Collisions counts and averages¶

| Categories | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Collision/Injuries outcomes at Intersections | |||||||

| Collisions | 47,611 | 95,437 | 94,644 | 97,792 | 68,511 | 78,764 | 58,942 |

| Injuries of: | |||||||

| Persons | 13,336 | 26,640 | 24,466 | 23,160 | 18,611 | 22,666 | 17,513 |

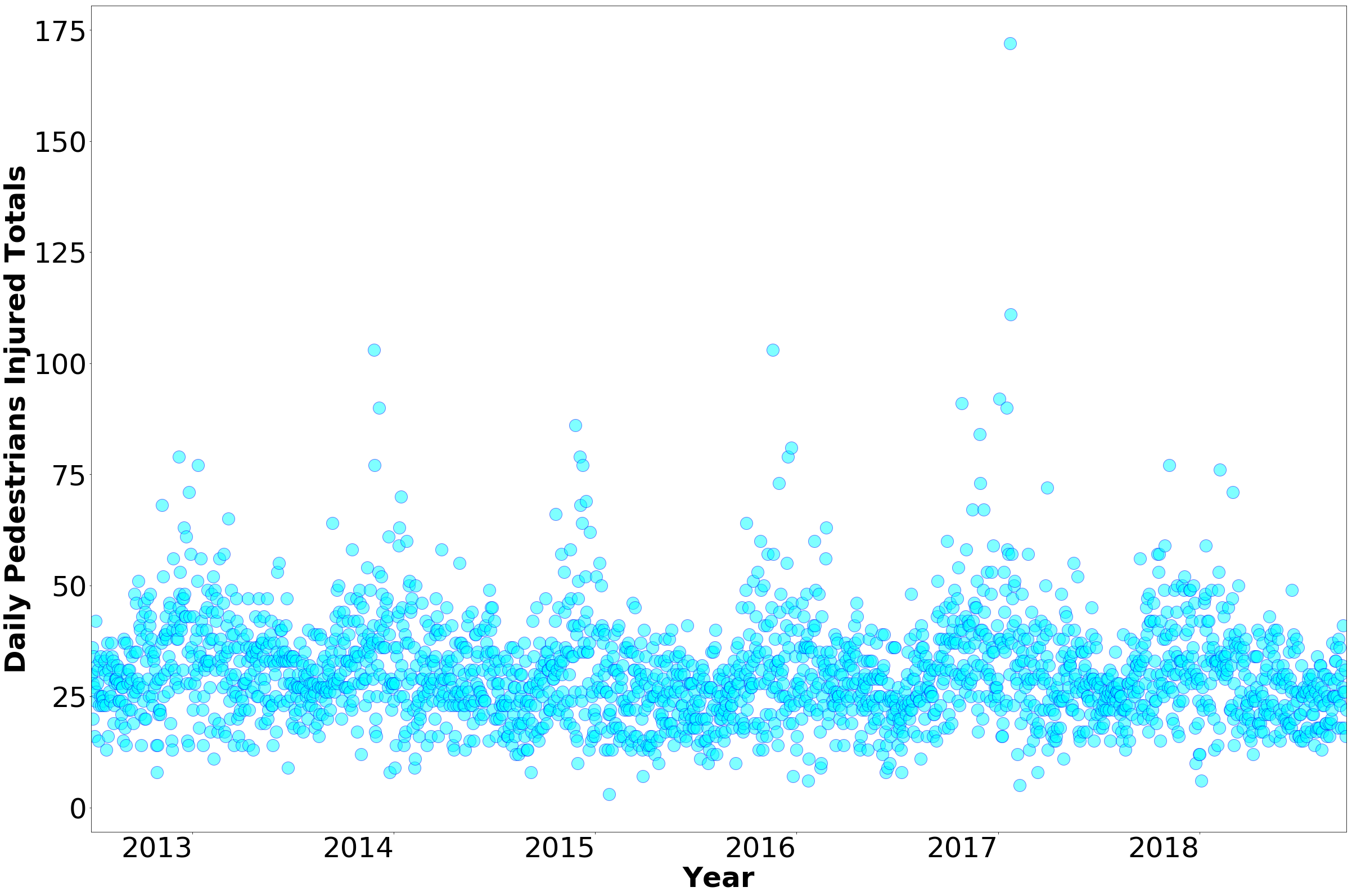

| Pedestrians | 3,725 | 7,555 | 6,859 | 6,095 | 4,821 | 5,781 | 3,942 |

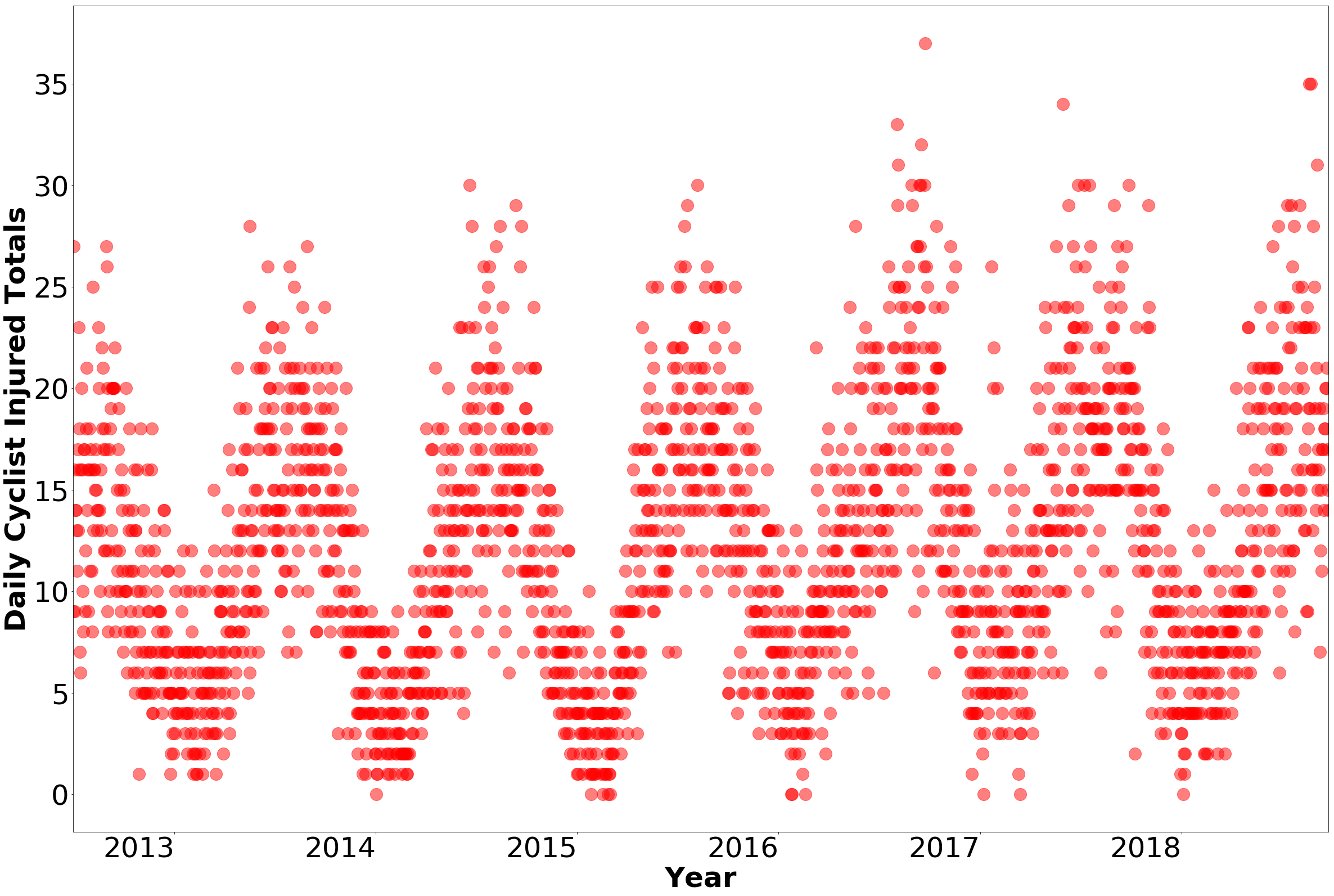

| Cyclist | 1,355 | 2,569 | 2,598 | 2,597 | 1,978 | 2,339 | 1,766 |

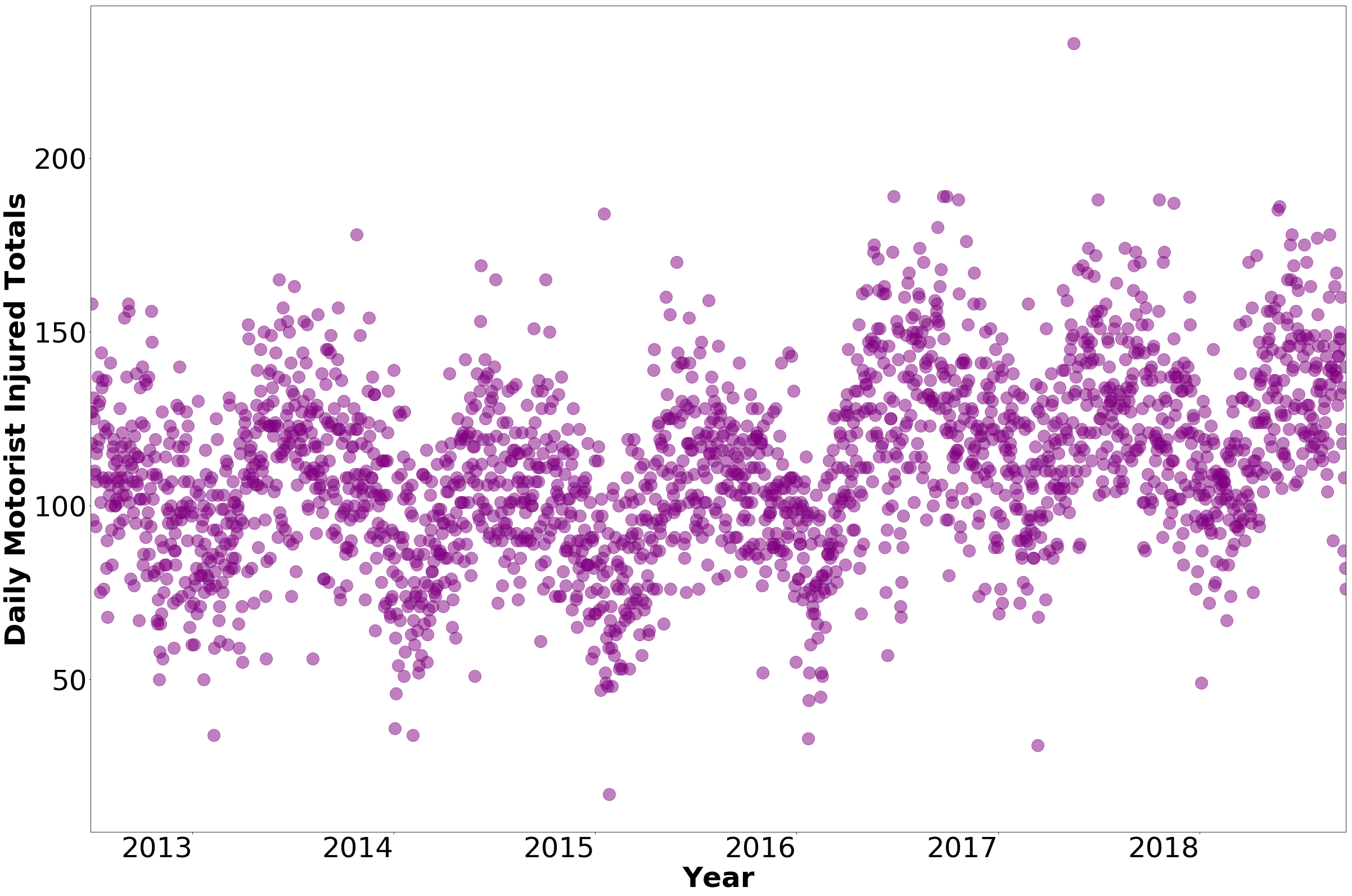

| Motorist | 8,250 | 16,516 | 15,008 | 14,468 | 11,911 | 14,967 | 11,706 |

| B. Collision/Injuries counts at Intersections Stratified by LPIs | |||||||

| LPIs Ever == 1 | 13,068 | 26,101 | 25,963 | 27,244 | 18,588 | 20,173 | 15,034 |

| LPIs Ever == 0 | 34,543 | 69,336 | 68,681 | 70,548 | 49,923 | 58,591 | 43,908 |

| C. Collision/Injuries averages at Intersections Stratified by LPIs | |||||||

| LPIs Ever == 1 | 2.43 | 2.43 | 2.41 | 2.53 | 1.73 | 1.88 | 1.86 |

| LPIs Ever == 0 | 1.68 | 1.68 | 1.67 | 1.71 | 1.21 | 1.42 | 1.42 |

Table 2: Collisions with longitude and latitude filled¶

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates Filled | 85,452 | 171,917 | 172,730 | 182,958 | 162,745 | 214,935 | 157,185 |

| (%) | -84.99 | -84.39 | -83.84 | -84.05 | -71.44 | -93.75 | -94.87 |

| Coordinates missing | 15,087 | 31,806 | 33,296 | 34,729 | 65,077 | 14,327 | 8,508 |

| (%) | -15.01 | -15.61 | -16.16 | -15.95 | -28.56 | -6.25 | -5.13 |

| Total | 0 | 13 | 60 | 408 | 713 | 825 | 670 |

Table 3: Number of LPIs implemented in Quarters and Years¶

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates Filled | 85,452 | 171,917 | 172,730 | 182,958 | 162,745 | 214,935 | 157,185 |

| (%) | -84.99 | -84.39 | -83.84 | -84.05 | -71.44 | -93.75 | -94.87 |

| Coordinates missing | 15,087 | 31,806 | 33,296 | 34,729 | 65,077 | 14,327 | 8,508 |

| (%) | -15.01 | -15.61 | -16.16 | -15.95 | -28.56 | -6.25 | -5.13 |

| Total | 0 | 13 | 60 | 408 | 713 | 825 | 670 |

Table 4: Characteristics of the intersections¶

| LPIs intersections | Control intersections | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of intersections in New York City | 2,689 | 10,298 |

| School (intersections within 200 feet of school) | 201 | 475 |

| -7.47% | -4.61% | |

| Seniors (intersections within safe senior zone) |

859 | 1,717 |

| -31.94% | -16.67% | |

| Priority Intersection (intersections within 10 ft of signal intersection) | 110 | 109 |

| -4.09% | -1.06% |

Table 5: Naive regression model - Number of collisions per quarter¶

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Poisson | OLS | Poisson Late night | OLS Late night | Poisson Non- Late night | OLS Non- Late night |

| Flag LPIs | 0.258*** | 0.447*** | 0.309*** | 0.0568*** | 0.252*** | 0.390*** |

| -0.0253 | -0.047 | -0.0383 | -0.00769 | -0.025 | -0.0415 | |

| Bike route | 0.239*** | 0.421*** | 0.362*** | 0.0644*** | 0.226*** | 0.357*** |

| -0.0219 | -0.0412 | -0.0301 | -0.00594 | -0.0216 | -0.0363 | |

| Street Improvement | 0.334*** | 0.707*** | 0.357*** | 0.0772*** | 0.332*** | 0.630*** |

| -0.0737 | -0.182 | -0.089 | -0.0224 | -0.0738 | -0.164 | |

| Left Turn | 0.519*** | 1.186*** | 0.449*** | 0.106*** | 0.527*** | 1.080*** |

| -0.0608 | -0.176 | -0.11 | -0.0327 | -0.0587 | -0.152 | |

| Observations | 324,675 | 324,675 | 324,675 | 324,675 | 324,675 | 324,675 |

Table 6: Fixed effect DiD model - Number of collisions per quarter¶

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Fixed effects poisson |

Fixed effects regression |

Fixed effects poisson Late night |

Fixed effects regression Late night |

Fixed effects poisson Non-Late night |

Fixed effects regression Non-Late night |

| Flag LPIs | -0.0545*** | -0.162*** | -0.00245 | -0.00039 | -0.0604*** | -0.161*** |

| -0.0128 | -0.0305 | -0.0255 | -0.00628 | -0.013 | -0.0279 | |

| Bike route | 0.0233 | 0.0521 | 0.0421 | 0.0101 | 0.0217 | 0.0434 |

| -0.0189 | -0.0379 | -0.04 | -0.00865 | -0.0189 | -0.0345 | |

| Street Improvement | -0.0157 | -0.209 | -0.0133 | -0.016 | -0.0172 | -0.195 |

| -0.0449 | -0.148 | -0.0661 | -0.0234 | -0.0458 | -0.135 | |

| Left Turn | -0.140*** | -0.806*** | -0.133* | -0.0683** | -0.139*** | -0.742*** |

| -0.0369 | -0.174 | -0.0741 | -0.0274 | -0.0384 | -0.162 | |

| Observations | 283,550 | 283,550 | 242,725 | 242,725 | 283,200 | 283,200 |

| Number of intersection_id | 11,342 | 11,342 | 9,709 | 9,709 | 11,328 | 11,328 |

| Number of intersection_id | 11,342 | 11,342 | 9,709 | 9,709 | 11,328 | 11,328 |

Table 7: Fixed effect DiD model - Number of persons injured per quarter¶

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Fixed effects poisson |

Fixed effects regression |

Fixed effects poisson Late night |

Fixed effects regression Late night |

Fixed effects poisson Non-Late night |

Fixed effects regression Non-Late night |

| Flag LPIs | -0.0993*** | -0.0692*** | -0.111** | -0.0145** | -0.0980*** | -0.0603*** |

| -0.0213 | -0.0134 | -0.054 | -0.00722 | -0.0221 | -0.0122 | |

| Bike route | 0.0169 | 0.01 | -0.00445 | -0.000199 | 0.0193 | 0.0103 |

| -0.0307 | -0.0166 | -0.0789 | -0.00986 | -0.0316 | -0.015 | |

| Street Improvement | -0.0272 | -0.041 | -0.106 | -0.0187 | -0.0167 | -0.0287 |

| -0.0545 | -0.0434 | -0.17 | -0.028 | -0.0557 | -0.0388 | |

| Left Turn | -0.200*** | -0.217*** | -0.25 | -0.0483* | -0.193*** | -0.185*** |

| -0.066 | -0.0623 | -0.156 | -0.0272 | -0.0675 | -0.0552 | |

| Observations | 273,875 | 273,875 | 146,725 | 146,725 | 272,000 | 272,000 |

| Number of intersection_id | 10,955 | 10,955 | 5,869 | 5,869 | 10,880 | 10,880 |

| Number of intersection_id | 11,342 | 11,342 | 9,709 | 9,709 | 11,328 | 11,328 |

Table 8: Fixed effect DiD model - Number of pedestrians injured per quarter¶

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Fixed effects poisson |

Fixed effects regression |

Fixed effects poisson Late night |

Fixed effects regression Late night |

Fixed effects poisson Non-Late night |

Fixed effects regression Non-Late night |

| Flag LPIs | -0.147*** | -0.0337*** | -0.0895 | -0.00493 | -0.153*** | -0.0329*** |

| -0.0289 | -0.00569 | -0.088 | -0.00529 | -0.0303 | -0.00547 | |

| Bike route | -0.0789* | -0.0129* | -0.0592 | -0.00251 | -0.0799* | -0.0123* |

| -0.0419 | -0.00749 | -0.131 | -0.00773 | -0.0445 | -0.00741 | |

| Street Improvement | -0.0391 | -0.0208 | -0.125 | -0.00877 | -0.0312 | -0.0168 |

| -0.0744 | -0.0194 | -0.236 | -0.0159 | -0.0849 | -0.02 | |

| Left Turn | -0.302*** | -0.147*** | -0.199 | -0.0198 | -0.311*** | -0.136*** |

| -0.0718 | -0.0264 | -0.204 | -0.0148 | -0.0804 | -0.0259 | |

| Observations | 223,100 | 223,100 | 58,475 | 58,475 | 218,675 | 218,675 |

| Number of intersection_id | 8,924 | 8,924 | 2,339 | 2,339 | 8,747 | 8,747 |

| Number of intersection_id | 11,342 | 11,342 | 9,709 | 9,709 | 11,328 | 11,328 |

Table 9: Fixed effect DiD model - Number of cyclists injured per quarter¶

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Fixed effects poisson |

Fixed effects regression |

Fixed effects poisson Late night |

Fixed effects regression Late night |

Fixed effects poisson Non-Late night |

Fixed effects regression Non-Late night |

| Flag LPIs | -0.0272 | -0.00275 | 0.0632 | 0.00269 | -0.0376 | -0.00357 |

| -0.0418 | -0.00431 | -0.13 | -0.00617 | -0.0437 | -0.00423 | |

| Bike route | 0.172*** | 0.0157*** | 0.0532 | 0.00229 | 0.184*** | 0.0161*** |

| -0.0643 | -0.00585 | -0.204 | -0.00951 | -0.0677 | -0.00584 | |

| Street Improvement | 0.0935 | 0.00912 | 0.252 | 0.0121 | 0.0788 | 0.00728 |

| -0.116 | -0.0125 | -0.33 | -0.0163 | -0.124 | -0.0125 | |

| Left Turn | -0.206* | -0.0309* | -0.291 | -0.0155 | -0.199 | -0.0272* |

| -0.122 | -0.0158 | -0.339 | -0.0186 | -0.133 | -0.0158 | |

| Observations | 158,275 | 158,275 | 27,575 | 27,575 | 152,775 | 152,775 |

| Number of intersection_id | 6,331 | 6,331 | 1,103 | 1,103 | 6,111 | 6,111 |

| Number of intersection_id | 11,342 | 11,342 | 9,709 | 9,709 | 11,328 | 11,328 |

Table 10: Fixed effect DiD model - Number of motorists injured per quarter¶

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Fixed effects poisson |

Fixed effects regression |

Fixed effects poisson Late night |

Fixed effects regression Late night |

Fixed effects poisson Non-Late night |

Fixed effects regression Non-Late night |

| Flag LPIs | -0.0856*** | -0.0362*** | -0.129* | -0.0163* | -0.0778** | -0.0284*** |

| -0.029 | -0.0119 | -0.0676 | -0.0084 | -0.0311 | -0.0109 | |

| Bike route | 0.0359 | 0.013 | 0.00446 | 0.000949 | 0.0399 | 0.0127 |

| -0.0419 | -0.0149 | -0.0974 | -0.0118 | -0.044 | -0.0136 | |

| Street Improvement | -0.0357 | -0.0271 | -0.12 | -0.0172 | -0.0216 | -0.0171 |

| -0.0751 | -0.0389 | -0.219 | -0.0322 | -0.0758 | -0.0337 | |

| Left Turn | -0.0792 | -0.0408 | -0.216 | -0.0319 | -0.0525 | -0.0236 |

| -0.103 | -0.0518 | -0.217 | -0.03 | -0.107 | -0.0461 | |

| Observations | 254,400 | 254,400 | 113,775 | 113,775 | 248,025 | 248,025 |

| Number of intersection_id | 10,176 | 10,176 | 4,551 | 4,551 | 9,921 | 9,921 |

| Number of intersection_id | 11,342 | 11,342 | 9,709 | 9,709 | 11,328 | 11,328 |

Table 11: Fixed effects DiD Spatial Lag Model of Manhattan Intersections¶

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Number of Collisions | Number of Person injured | Number of Pedestrians injured | Number of Cyclists injured | Number of Motorist Injured |

Flag LPIs |

-0.106*** | -0.0643*** | -0.0389*** | -0.0166*** | -0.00897 |

| -0.0377 | -0.0176 | -0.00894 | -0.00569 | -0.0137 | |

| W.outcome | 0.188*** | 0.0171** | 0.00064 | 0.0320*** | 0.0134* |

| -0.00628 | -0.00709 | -0.00714 | -0.00705 | -0.00713 | |

| Impact | |||||

| Direct | -0.106*** | -0.064*** | -0.039*** | -0.017*** | -0.009 |

| 0.038 | 0.018 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.014 | |

| Indirect | -0.022*** | -0.001** | 0 | -0.001** | 0 |

| 0.008 | 0.001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | -0.128*** | -0.065*** | -0.039*** | -0.017*** | -0.009 |

| 0.046 | 0.018 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.014 | |

| Observations | 68,400 | 68,400 | 68,400 | 68,400 | 68,400 |

| Number of intersection_id | 2,736 | 2,736 | 2,736 | 2,736 | 2,736 |

Table 12: Fixed effects DiD Spatial Error Model of Manhattan Intersections¶

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Number of Collisions | Number of Person injured | Number of Pedestrians injured | Number of Cyclists injured | Number of Motorist Injured |

| Flag LPIs | -0.129*** | -0.0644*** | -0.0389*** | -0.0168*** | -0.00893 |

| -0.0387 | -0.0176 | -0.00894 | -0.00572 | -0.0138 | |

| e.outcome | 0.188*** | 0.0150** | -0.00143 | 0.0319*** | 0.0129* |

| -0.00639 | -0.00713 | -0.00718 | -0.00707 | -0.00714 | |

| Observations | 68,400 | 68,400 | 68,400 | 68,400 | 68,400 |

| Number of intersection_id | 2,736 | 2,736 | 2,736 | 2,736 | 2,736 |

Table 13: Fixed effects DiD Non-Spatial Model of Manhattan Intersections¶

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Number of Collisions | Number of Person injured | Number of Pedestrians injured | Number of Cyclists injured | Number of Motorist Injured |

| 1.flag_LPIS | -0.089 | -0.0644*** | -0.0389*** | -0.0166** | -0.00906 |

| -0.0679 | -0.0208 | -0.0109 | -0.00662 | -0.0153 | |

| bike_route_tv | 0.177** | 0.0265 | -0.011 | 0.00352 | 0.0361* |

| -0.088 | -0.025 | -0.0128 | -0.00735 | -0.0189 | |

| flag_street_improv | -0.453 | -0.0712 | -0.0457 | 0.00515 | -0.0297 |

| -0.301 | -0.0638 | -0.0301 | -0.0198 | -0.0461 | |

| flag_left_turn | -0.999*** | -0.291*** | -0.168*** | -0.0284 | -0.0966 |

| -0.328 | -0.0924 | -0.0494 | -0.025 | -0.0604 | |

| Observations | 68400 | 68400 | 68400 | 68400 | 68400 |

| R-squared | 0.089 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.01 | 0.006 |

| Number of _ID | 2736 | 2736 | 2736 | 2736 | 2736 |

References¶

Ajilore, O. (2015). Identifying peer effects using spatial analysis: the role of peers on risky sexual behavior. Review of Economics of the Household, 13(3), 635–652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9235-4

Anselin, L. (1988). Spatial Econometrics: Methods and Models. In Studies in Operational Regional Science. Retrieved from https://www.springer.com/us/book/9789024737352

Anselin, L., & Griffith, D. A. (1988). Do spatial effects really matter in regression analysis? Papers - Regional Science Association, 65, 11–34.

Appendix A - Crash Cost Estimates by Maximum Police-Reported Injury Severity Within Selected Crash Geometries, October 2005 - FHWA-HRT-05-051. (n.d.). Retrieved March 16, 2019, from https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/research/safety/05051/06.cfm

Fayish, A., & Gross, F. (2010). Safety Effectiveness of Leading Pedestrian Intervals Evaluated by a Before-After Study with Comparison Groups. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2198, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.3141/2198-03

Goodman-Bacon, A. (2018). Difference-in-Differences with Variation in Treatment Timing (No. w25018). https://doi.org/10.3386/w25018

Goughnour, E., Carter, D., Lyon, C., Persaud, B., Lan, B., Chun, P., … Signor, K. (2018). Safety Evaluation of Protected Left-Turn Phasing and Leading Pedestrian Intervals on Pedestrian Safety (No. FHWA-HRT-18-044). U.S. Department of Transportation.

Goughnour, Elissa, Carter, D., Lyon, C., Persaud, B., Lan, B., Chun, P., … Signor, K. (n.d.). Safety Evaluation of Protected Left-Turn Phasing and Leading Pedestrian Intervals on Pedestrian Safety. Retrieved from https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/research/safety/18044/18044.pdf

Hauer, E., Harwood, D. W., Council, F. M., & Griffith, M. S. (2002). Estimating Safety by the Empirical Bayes Method: A Tutorial. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1784(1), 126–131. https://doi.org/10.3141/1784-16

Hubbard, S. M. L., Bullock, D. M., & Thai, J. H. (2008). Trial Implementation of a Leading Pedestrian Interval: Lessons Learned. ITE Journal, 78(10). Retrieved from https://trid.trb.org/view/873717

King, M. R. (2000). CALMING NEW YORK CITY INTERSECTIONS. Transportation Research Circular. Presented at the Urban Street Symposium Transportation Research Board; American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials; American Society of Civil Engineers; Federal Highway Administration; Institute of Transportation Engineers; and National Association of County Engineers. Retrieved from https://trid.trb.org/view/686665

LeSage, J., Pace, R. K., & Pace, R. K. (2009). Introduction to Spatial Econometrics. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420064254

Matyas, L., & Sevestre, P. (Eds.). (2008). The Econometrics of Panel Data: Fundamentals and Recent Developments in Theory and Practice (3rd ed.). In (3rd ed.). Retrieved from https://www.springer.com/us/book/9783540758891

NYC DOT. (2014). Vision Zero Action Plan 2014. Retrieved from http://www.nyc.gov/html/visionzero/pdf/nyc-vision-zero-action-plan.pdf

NYC DOT. (n.d.). NYC DOT - Data Feeds. Retrieved February 20, 2019, from https://www1.nyc.gov/html/dot/html/about/datafeeds.shtml

NYC DOT - Leading Pedestrian Interval Signals. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2018, from http://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/html/infrastructure/leading-ped-intervals.shtml

NYC Open Data, O. (2018, December 2). NYPD Motor Vehicle Collisions | NYC Open Data. Retrieved December 2, 2018, from /Public-Safety/NYPD-Motor-Vehicle-Collisions/h9gi-nx95, /Public-Safety/NYPD-Motor-Vehicle-Collisions/h9gi-nx95

NYS DMV. (n.d.). Motorist accident reports | New York State Department of Motor Vehicles. Retrieved February 20, 2019, from https://dmv.ny.gov/dmv-records/motorist-accident-reports

Open Data Law - DoITT. (2019, February 16). Retrieved February 16, 2019, from https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doitt/initiatives/open-data-law.page

Pécheux, K., Bauer, J., & McLeod, P. (2009). Pedestrian Safety Engineering and ITS-Based Countermeasures Program for Reducing Pedestrian Fatalities, Injury Conflicts, and Other Surrogate Measures Final System Impact Report. Retrieved from Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) website: https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/ped_bike/tools_solve/ped_scdproj/sys_impact_rpt/sys_impact_rpt.pdf

Rhee, K.-A., Kim, J.-K., Lee, Y., & Ulfarsson, G. F. (2016). Spatial regression analysis of traffic crashes in Seoul. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 91, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2016.02.023

Sharma, A., Smaglik, E. J., Kothuri, S., Smith, O., Koonce, P., & Huang, T. (2017). Leading pedestrian intervals treating the decision to implement as a marginal benefit–Cost problem. Traffic Signal Systems, Volume 2, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.3141/2620-09

Tchoukanski, I. (n.d.). Thiessen Polygons. Retrieved March 4, 2019, from https://www.ian-ko.com/ET_GeoWizards/UserGuide/thiessenPolygons.htm

Van Houten, R., Retting, R. A., Farmer, C. M., & Van Houten, J. (2000). FIELD EVALUATION OF A LEADING PEDESTRIAN INTERVAL SIGNAL PHASE AT THREE URBAN INTERSECTIONS. Transportation Research Record, (1734). Retrieved from https://trid.trb.org/view/671706

Wing, C., Simon, K., & Bello-Gomez, R. A. (2018). Designing Difference in Difference Studies: Best Practices for Public Health Policy Research. Annual Review of Public Health, 39(1), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013507